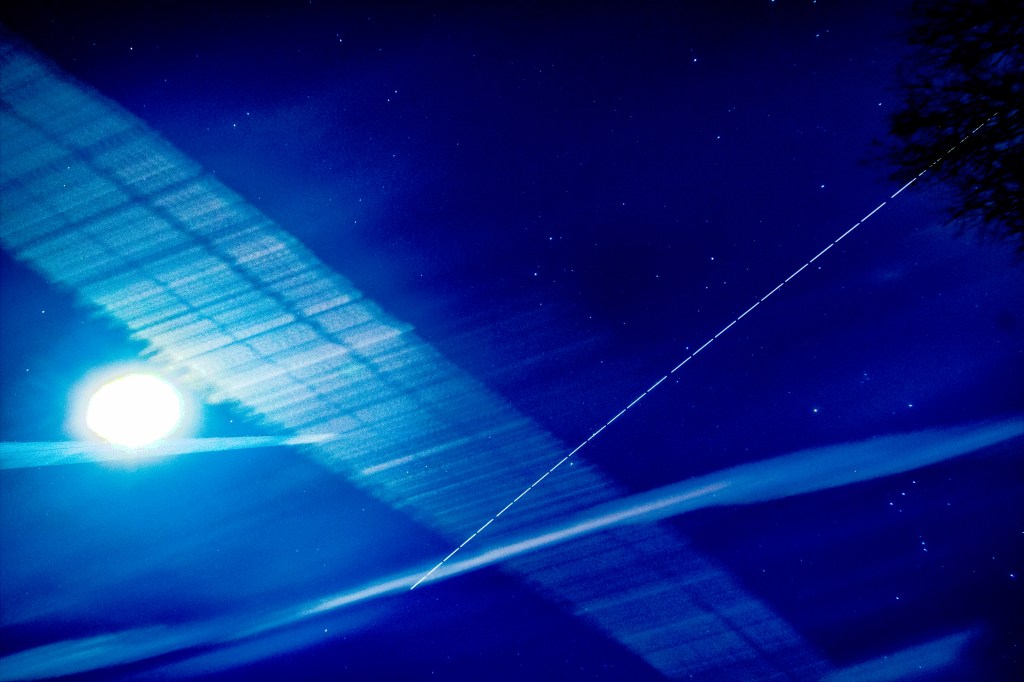

It was a bright and hazy night (I’ve always wanted to use that line). The mission (should I choose to accept) is to image the International Space Station as it plows into the moon. Reliable data from the National Aeronautics Space Administration indicates its path is on prefect trajectory, west northwest to southeast, to intercept the moon, beginning at 8:47 DST (daylight stupid time).

Well, it seems that someone, either the folks driving the ISS or whoever controls the movement of the moon, were a bit off track. With my trusty assistant, Les, and his new camera that is secondarily a cell phone, we watched ISS smoothly move along and miss the moon by several thousand miles. This is good and bad news.

To get this image I stacked 50 images (really only needed about half that many) and used a couple different stacking programs. The lesson here, is, putting the same data into different programs yields different results. Or, garbage in, garbage out. The first image is from the usual stacking program. The fact that ISS presents as a dashed line does not mean “cut here.” The spaces are the fraction of time between exposures. Note how the line stops, for no known reason. The second image I created by putting the same data into the program for imaging comets. Why? Because I could and wanted to see what would happen. Note how the damn contrails are sharper (the moon less so), the image of ISS varies in brightness, and the whole path of ISS is recorded. On the lower right side you can see the constellation of Orion (at least his belt and sword). These images were made with my Nikon D7500 and 10mm ultra wide angle lens. I think the difference of light intensity in the second image is probably accurate. The space station rotates and light is not reflected equally from all sides.

The third image is your bonus for staying with me through all this. It’s a nightscape shot with Orion in the lower center. And, of course, we got photo-bombed by an airplane. The bright star at the lower left is Siris, brightest in the sky.